Johann Heinrich Von Bernstorff on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

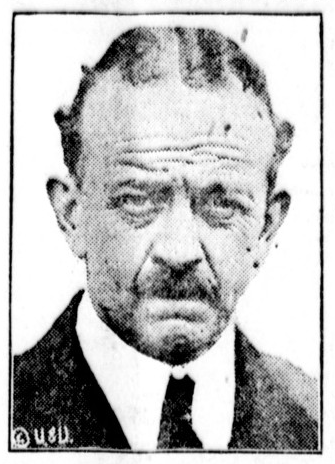

Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff (14 November 1862 – 6 October 1939) was a German politician and

In 1908, Bernstorff was appointed the German ambassador to the United States.

He was recalled to Germany on 7 July 1914 but returned on 2 August, upon the outbreak of the

In 1908, Bernstorff was appointed the German ambassador to the United States.

He was recalled to Germany on 7 July 1914 but returned on 2 August, upon the outbreak of the

Bernstorff was proposed as Foreign Minister in

Bernstorff was proposed as Foreign Minister in

''My three years in America''

(New York: Scribner's, 1920) * ''Memoirs of Count Bernstorff'' (New York: Random House, 1936)

Bernstorff

next to

Bernstorff, Johann Heinrich, Graf von

in

* ttps://books.google.com/books?id=ujMXLDE8RBwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Johann+heinrich+bernstorff&lr=&as_brr=3#v=onepage&q=&f=false My Three Years in Americaby Johann Heinrich Bernstorff {{DEFAULTSORT:Bernstorff, Johann Heinrich Von 1862 births 1939 deaths People from London German Protestants German Democratic Party politicians Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic Counts of Germany German people of World War I Hindu–German Conspiracy Emigrants from Nazi Germany to Switzerland Ambassadors of Germany to the United States Ambassadors of Germany to the Ottoman Empire Witnesses of the Armenian genocide World War I spies for Germany People stripped of honorary degrees

ambassador to the United States

The following table lists ambassadors to the United States, sorted by the representative country or organization.

See also

*Ambassadors of the United States

Notes

{{reflist, 30em

External linksCurrent and former Ambassadors to the United Sta ...

from 1908 to 1917.

Early life

Born in 1862 in London, he was the son of one of the most powerful politicians in thePrussian Kingdom

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. R ...

. As Foreign Minister for Prussia, his father, Count Albrecht von Bernstorff

Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff (22 March 1809 – 26 March 1873) was a Prussian statesman.

Early life

Bernstorff was born at the estate Dreilützow (now in the municipality of Wittendörp), in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. He was a so ...

, had earned the ire of Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

in the Prussian constitutional crisis of 1859–1866. Overestimating his political strength, Bernstorff resigned in a spat over the constitution with the expectation to force his will on the Prussian government. However, the Emperor accepted Bernstorff's miscalculated challenge and appointed Bismarck chancellor and foreign minister. For the rest of his life, Bernstorff would criticise Bismarck's Machiavellian style of governing. In 1862, the elder Bernstorff served as ambassador to the Court of St James's

The Court of St James's is the royal court for the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. All ambassadors to the United Kingdom are formally received by the court. All ambassadors from the United Kingdom are formally accredited from the court – & ...

. For the next eleven years, the young Bernstorff grew up in England until his father's death, in 1873. After moving back to Germany, he went to the humanistic gymnasium in Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

from which he graduated with a baccalaureate in 1881.

While Bernstorff's dream had always been to pursue a diplomatic career, the family feud with Bismarck made an appointment to the diplomatic service impossible. As a result, he joined the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

for the next eight years and served in an artillery unit in Berlin.

After being elected a member of the Reichstag, he finally succeeded in convincing the Bismarcks to settle the dispute with the long-dead father. In 1887, von Bernstorff married Jeanne Luckemeyer, a German-American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

. She was a native of New York City and daughter of a wealthy silk merchant.

Career

First diplomatic postings

His first diplomatic assignment wasConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, where he served as military attaché. From 1892 to 1894, he served at the German embassy in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

. After a brief assignment to St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(1895–1897), Bernstorff was stationed in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

for a period. He then became First Secretary of the German embassy in London (1902–1906). Bernstorff's diplomatic skills were noted in Berlin throughout the First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis or the Tangier Crisis was an international crisis between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. Germany wanted to challenge France's growing control over Morocco, aggravating France and Great Britain. The ...

in 1905. He then served as consul general in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

(1906–1908).

Despite his family's problems with the Bismarcks, Bernstorff basically agreed with Bismarck's policies, particularly the decision to found the German Reich without Austria in 1871. As a diplomat, Bernstorff adamantly supported Anglo-German rapprochement and considered the policies of Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

"reckless".

Ambassador to the United States

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. It was later revealed that he had been recruited into intelligence work and ordered to assist the German war effort by all means necessary. He was also provided with a large slush fund

A slush fund is a fund or account that is not properly accounted, such as money used for corrupt or illegal purposes, especially in the political sphere. Such funds may be kept hidden and maintained separately from money that is used for legitim ...

to finance those operations. He began with attempts to assist German-Americans who wished to return home to fight by forging passports to get them through the Allied blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

.

Publicly, Bernstorff's ambassadorship in Washington was characterised by a diplomatic battle with the British ambassador, Sir Cecil Spring Rice

Sir Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, (27 February 1859 – 14 February 1918) was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1912 to 1918, as which he was responsible for the organisation of British efforts to end A ...

, with both men attempting to influence the American government's position regarding the war. Later, however, as the blockade began to prevent American munitions manufacturers from trading with Germany, Bernstorff began financing sabotage missions to obstruct arms shipments to Germany's enemies. Some of the plans included a September 1914 attempt at destroying the Welland Canal

The Welland Canal is a ship canal in Ontario, Canada, connecting Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. It forms a key section of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Great Lakes Waterway. Traversing the Niagara Peninsula from Port Weller in St. Catharines t ...

, which circumvents Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

. That year, the German diplomatic mission also began supporting the expatriate Indian movement for independence.

Bernstorff was assisted by Captain Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

, later a German chancellor, and Captain Karl Boy-Ed Karl may refer to:

People

* Karl (given name), including a list of people and characters with the name

* Karl der Große, commonly known in English as Charlemagne

* Karl Marx, German philosopher and political writer

* Karl of Austria, last Austria ...

, a naval attaché. The commercial attaché, Heinrich Albert

Heinrich Friedrich Albert (12 February 1874 to 1 November 1960) was a German civil servant, diplomat, politician, businessman and lawyer who served as minister for reconstruction and the Treasury in the government of Wilhelm Cuno in 1922/1923. ...

, was the finance officer for the sabotage operations. Papen and the German consulate in San Francisco were known to have been extensively involved in the Hindu–German Conspiracy

The Indo–German Conspiracy (Note on the name) was a series of attempts between 1914 and 1917 by Indian nationalist groups to create a Pan-Indian rebellion against the British Empire during World War I. This rebellion was formulated betwee ...

, especially in the ''Annie Larsen'' gun-running plot. Although Bernstorff himself officially denied all knowledge, most accounts agree that he was intricately involved as part of the German intelligence and sabotage offensive in America against Britain. After the capture of the and confiscation of its cargo, Bernstorff made efforts to recover the $200,000 worth of arms and insisted that they were meant for Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck (20 March 1870 – 9 March 1964), also called the Lion of Africa (german: Löwe von Afrika), was a general in the Imperial German Army and the commander of its forces in the German East Africa campaign. For four ye ...

in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozam ...

. That was futile, however, and the arms were auctioned off.

In December 1914, a humorous British article on his activities in the United States, ''The Amazing Ambassador'', by P.G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, ( ; 15 October 188114 February 1975) was an English author and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Jee ...

, was published in the ''Sunday Chronicle'' on 13 December 1914. That month also saw Bernstorff receive a cable from the German Foreign Office that instructed him to target the Canadian railways. On 1 January 1915, the Roebling Wire and Cable plant in Trenton, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, was blown up. On 28 January, an American merchant ship carrying wheat to Britain was sunk. On 2 February 1915, Lieutenant Werner Horn was captured after the Vanceboro international bridge bombing

The 1915 Vanceboro international bridge bombing was an attempt to destroy the Saint Croix-Vanceboro Railway Bridge on February 2, 1915, by Imperial German spies.

This international bridge crossed the St. Croix River between the border hamlets of ...

. In 1916, his wife was involved in blackmail plot by a former German spy, Armgaard Karl Graves.

In 1915, Bernstorff also helped organise what became known as the Great Phenol Plot, an attempt to divert phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it req ...

from the production of high explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

in the United States, which would end up being sold to the British, and to prop up several German-owned chemical companies that made aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

and its precursor, salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4CO2H. A colorless, bitter-tasting solid, it is a precursor to and a metabolite of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid). It is a plant hormone, and has been listed by the EPA Toxic Substance ...

. In September 1915, his agents attempted to influence the negotiations between American banks and the Anglo-French Financial Commission

The Anglo-French Financial Commission was a special delegation to the United States from the governments of the United Kingdom and France in 1915 during the First World War. The Commission, led by Lord Reading, secured the single largest loan from ...

but failed to prevent an agreement from being reached.

In July 1916, the Black Tom explosion

The Black Tom explosion was an act of sabotage by agents of the German Empire, to destroy U.S.-made munitions that were to be supplied to the Allies of World War I, Allies in World War I. The explosions, which occurred on July 30, 1916, in New Y ...

was the most spectacular of the sabotage operations.

Some of Bernstorff's other activities were exposed by the British Secret Service, which had obtained and distributed to the press a photograph of him "in a swimming costume with his arms around two similarly dressed women, neither of whom was his wife".

Bernstorff was returned home on 3 February 1917, when US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

severed diplomatic relations with Germany after the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to sea ...

. Upon receiving the news, Colonel Edward M. House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

wrote to him, "The day will come when people in Germany will see how much you have done for your country in America".

In 1910, Brown University

Brown University is a private research university in Providence, Rhode Island. Brown is the seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, founded in 1764 as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providenc ...

had conferred an honorary Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor (LL. ...

degree on Bernstorff. At the school's commencement in 1918, while the war was going on, University President William Faunce read a resolution of the board of fellows revoking the degree because "while he was Ambassador of the Imperial German Government to the United States and while the nations were still at peace, ernstorffwas guilty of conduct dishonorable alike in a gentleman and a diplomat".

Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire

He assumed his position as ambassador to theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in 1917. Bernstorff conceded that the Ottoman policy against the Armenians was one of exterminating the race. Bernstorff provided a detailed account of the massacres in his memoirs, ''Memoirs of Count Bernstorff''. In his memoirs, Bernstorff recounts a conversation with Talat Pasha after the massacres had been concluded: "When I kept on pestering him about the Armenian question, he once said with a smile: 'What on earth do you want? The question is settled, there are no more Armenians.'"

Weimar Republic

Bernstorff was proposed as Foreign Minister in

Bernstorff was proposed as Foreign Minister in Philipp Scheidemann

Philipp Heinrich Scheidemann (26 July 1865 – 29 November 1939) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). In the first quarter of the 20th century he played a leading role in both his party and in the young Weimar ...

's cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

in 1919, but he refused that post and left the diplomatic service. He became a founding member of the German Democratic Party

The German Democratic Party (, or DDP) was a center-left liberal party in the Weimar Republic. Along with the German People's Party (, or DVP), it represented political liberalism in Germany between 1918 and 1933. It was formed in 1918 from the ...

(''Deutsche Demokratische Partei'') and a member of the German Parliament

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Common ...

in 1921 to 1928. He was the first President of the German Association for the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, President of the World Federation of Associations of the League of Nations and a member of every German delegation to the League of Nations.

In 1926, he became the Chairman of Kurt Blumenfeld

Kurt Blumenfeld (May 29, 1884 – May 21, 1963) was a German-born Zionist from Marggrabowa, East Prussia. He was the secretary general of the World Zionist Organization from 1911 to 1914. He died in Jerusalem.

He had served as secretary of ...

's Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

German Pro-Palestine Committee (''Deutsches Pro-Palästina Komitee'') to support the foundation of a Jewish State in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

.

From 1926 to 1931, he was the chairman of the German delegation to the Preparatory World Disarmament Conference

The Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments, generally known as the Geneva Conference or World Disarmament Conference, was an international conference of states held in Geneva, Switzerland, between February 1932 and November 1934 ...

.

Bernstorff, who was explicitly mentioned by Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

as one of those men bearing "the guilt and responsibility for the collapse of Germany", left Germany in 1933 after the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

had risen to power and moved to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where he died on 6 October 1939.

Publications

''My three years in America''

(New York: Scribner's, 1920) * ''Memoirs of Count Bernstorff'' (New York: Random House, 1936)

See also

*Witnesses and testimonies of the Armenian genocide

Witnesses and testimony provide an important and valuable insight into the events which occurred both during and after the Armenian genocide. The Armenian genocide was prepared and carried out by the Ottoman government in 1915 as well as in the ...

* Foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt administration The foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt administration covers American foreign policy from 1901 to 1909, with attention to the main diplomatic and military issues, as well as topics such as immigration restriction and trade policy. For the adm ...

* Foreign policy of the Woodrow Wilson administration

Notes

References

External links

Bernstorff

next to

Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

in 1926 at the foundation of the pro-Palestine Committee

* Hoser, PaulBernstorff, Johann Heinrich, Graf von

in

* ttps://books.google.com/books?id=ujMXLDE8RBwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Johann+heinrich+bernstorff&lr=&as_brr=3#v=onepage&q=&f=false My Three Years in Americaby Johann Heinrich Bernstorff {{DEFAULTSORT:Bernstorff, Johann Heinrich Von 1862 births 1939 deaths People from London German Protestants German Democratic Party politicians Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic Counts of Germany German people of World War I Hindu–German Conspiracy Emigrants from Nazi Germany to Switzerland Ambassadors of Germany to the United States Ambassadors of Germany to the Ottoman Empire Witnesses of the Armenian genocide World War I spies for Germany People stripped of honorary degrees